Michel Majerus x Destino

Michel Majerus turned the canvas into a corrupted interface—layering fragments of pop, code, and gesture to expose the static beneath our visual culture’s polished sheen.

Michel Majerus didn’t paint images. He painted overload. His canvases weren’t windows to the world but screens—flickering, fragmented, and too fast to hold still. Born in Luxembourg in 1967 and gone by 2002, his short life yielded a body of work that feels more prophetic with each passing scroll. He wasn’t documenting pop culture; he was infected by it, and he let that infection mutate the very DNA of painting.

Majerus’s work doesn’t belong to the lineage of Pop Art in any nostalgic sense. There’s no Warholian distance, no ironic cool. Instead, there’s speed, urgency, and collapse. His paintings swallow Super Mario, Nike swooshes, techno fonts, and art history references, but they never digest them. These elements remain raw, flattened into the same visual plane, resisting any hierarchy. The result is a kind of pictorial white noise: seductive, violent, and impossible to parse linearly.

There’s a physicality to Majerus’s practice that contradicts the digital iconography he plunders. His brushstrokes are present—sloppy, gestural, alive. But they exist alongside pixels, slogans, and clip-art detritus. In works like Halbzeit, the hand of the painter glitches like a corrupted file. The canvas becomes a site of interference rather than expression, a corrupted download of culture’s collective unconscious.

What makes Majerus radical is not just what he paints, but how he thinks about painting. He dissolves authorship, quotes without reverence, loops rather than composes. His work doesn’t try to make sense of the image economy—it accelerates it to the point of rupture. This is painting as bandwidth, as feedback loop, as visual spam.

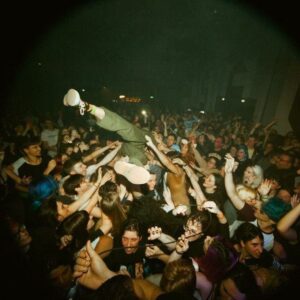

In his monumental installations—such as his Venice Biennale façade or the skateboard halfpipe covered in imagery—Majerus expands the logic of the screen into physical space. His environments don’t invite contemplation; they overwhelm. You are not meant to stand still before them, but to move, scroll, flick your eyes like you would through an infinite feed.

When he died in a plane crash at age 35, Majerus left behind not only a disrupted legacy but an unresolved one. He didn’t offer answers, only overload. Yet within that static, there’s a signal—a radical insistence that painting, even in the face of digital annihilation, could still absorb, reflect, and distort the now.

Today, in an age where everything has been templated, compressed, and optimized, his work feels less like a relic of the turn of the millennium and more like a glitch from the future—a reminder that the screen never replaced the canvas, it just became one.